Issue

Multiple studies have shown that high-touch surfaces1, such as bed rails, over bed tables, and other surfaces in the near patient environment, play a role in the transmission of pathogens to susceptible patients2,3. Annually, it is estimated that 1.7 million patients4 in the US acquire a Healthcare Associated Infection (HAI), resulting in increased hospitalizations, longer stay, 99,000 deaths, and additional costs of up to $40 billion.

Recent studies demonstrated that current cleaning practices result in high-touch surfaces being adequately cleaned less than half the time5. Additional studies6 have shown that improvements in cleaning compliance can be achieved by an intervention bundle that can include process improvements, feedback to cleaning staff and the use of fluorescent marking devices to provide proof of process compliance. While there are no validated standardized practices for cleaning and disinfection (CD) of high touch surfaces in patient rooms, there are recommended processes, but these processes differ significantly in complexity, detail, and requirements.

While in countries such as Canada and the UK, the government provides specific processes for Healthcare facilities to follow, in the US there is an absence of specific regulatory requirements or recommendations, thus pushing responsibility for development of an effective acute care cleaning program to the facility Environmental Services Director and Infection Preventionist.

Thus, it was a working assumption that the facility-to-facility variability in cleaning practices would be significant. Therefore, we conducted an audit of cleaning practices of high touch surfaces in acute care facilities to identify current process gaps and consequently developed a model for CD of a patient room using an audit tool created for this purpose.

Project

We conducted a study of current patient room CD practices in 10 acute care facilities (132 to 513 beds) in the US using a survey tool. Between June and August 2011, a two part survey was administered. In part 1, we interviewed the environmental services (EV) director at each facility. The survey included questions to identify what was being used by the EV staff for CD and for staff training:

- Cleaning tools (cloths, carts, hand tools, etc)

- Disinfectant and cleaning chemicals

- Methods and process for cleaning including specifi c surfaces to be cleaned

- Variation in methodology/process for specifi c pathogens

- Time allowed for various types of cleaning

- Training and documentation of the cleaning process, and methods

- Key challenges in performing healthcare cleaning

For the observation of actual practice in part 2, two patient rooms at each facility were randomly selected to observe the CD process and to document inconsistencies between policy and actual practice. Data from the study was tabulated and analysed.

Results and Discussion

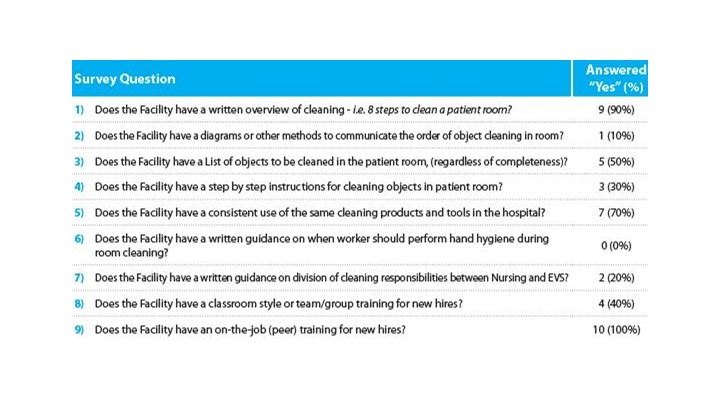

Table 1 shows the results of the survey. The most significant findings of the survey are as follows.

Very few facilities had detailed training materials (10 per cent) and programs to provide a worker with specifics on the cleaning process they were expected to follow. Only 50 per cent of the facilities had lists of all the objects to clean in a room.

None of the facilities has specifics in their training on when the worker was to perform hand hygiene, which is generally considered an important factor in preventing cross contamination.

Few facilities (20 per cent) had clear delineations between the responsibilities of EVS and Clinical Staff or had step-by-step instructions for cleaning objects in a patient room. Objects, such as IV poles, were shown to be infrequently cleaned due to this ambiguity of responsibility.

All facilities (100 per cent) used "on the job" training for new employees and have the high level cleaning process identified in writing, but there is little evidence of competency based training to use in evaluating the work done by the cleaners. In addition, there was a limited number of facilities performing process validation audits using validation tools. The most consistent evaluation of the workers performance was simply "does it look clean!".

Lessons Learned

Our study showed wide variations in current CD practices, with tools, processes, and training.

It also showed that CD responsibilities were not clearly delineated or documented, which led to wide variances in actual practice. We believe that this lack of documentation and specificity plays a significant role in the room to room and worker to worker variability in performing cleaning of high touch surface in patient room cleaning. In our opinion, this may be a significant contributing factor in the risk of pathogen transmission from environmental surfaces, resulting in Healthcare-Associated Infections for patients.

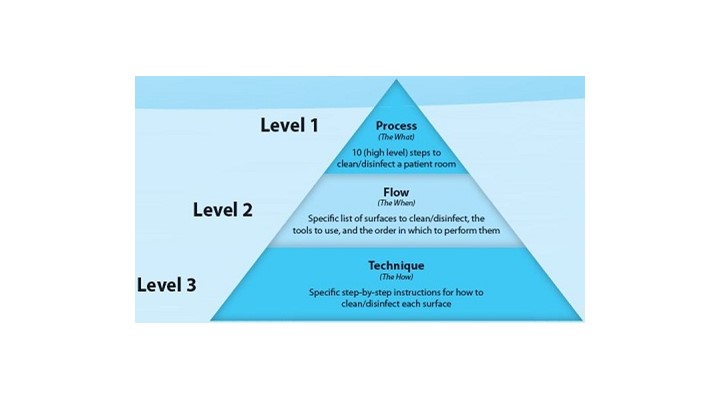

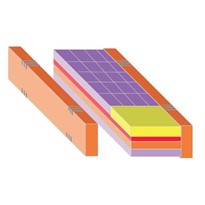

To bridge gaps identified during the survey, the information gathered was subsequently used to develop a programmatic multi-level model for patient room cleaning (see Figure 1) centered on the concept of Process (what to do), Flow (in what order to do it), and Technique (how to do it), which is our model to specifically identify the key tasks to be performed during patient room cleaning.

References:

- Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Miller MB, Huslage K, Sickbert-Bennett E. Role of hospital surfaces in the transmission of emerging healthcare associated pathogens; Norovirus, Clostridium diffi cile, and Acinetobacter species. Am J Infect Control 2010;38,S25-33.

- Huang SS, Datta R, Platt R. Risk of acquiring antibiotic-resistant bacteria from prior room occupants. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1945-1951.

- Drees M, et. Al. Prior environmental contamination increases the risk of acquisition of Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. CID 2008;46,678-685.

- Klevens RM, et al. Estimated health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. CDC Public Health Reports 2007;122,160-166.

- Carling PC, Parry MF, Von Beheren SM. Identifying opportunities to enhance environmental cleaning in 23 acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29,1-7.

- Carling PC, et. Al. Improving cleaning of the environment surrounding patients in 36 acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29,1035-1041.